Written by: Mark Russell

Art by: Steve Pugh

“Racism is the most expensive luxury we have,” Fred Flintstone says in a moment of reflection. Russell’s writing frequently cuts to the heart of social and cultural judgments and critiques. Frequently it strikes a meaningful tone that reflects back on modern society, but occasionally it stumbles and softens the impact of that critique. The Flintstones issue #10 attempts to juggle four different story lines, but only two of which reinforce the commentary central to this issue.

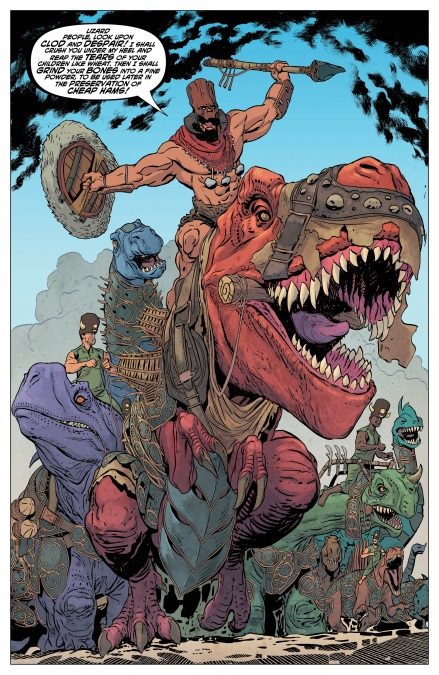

The newly elected manor of Bedrock discovers that political leadership focused on saber rattling and inflating international threats is easier than governing the services that impact citizens daily lives. After the loss of hospitals, social support structures, and retirement savings the people of Bedrock realize the value of governmental services that are not flashy or exciting. It is at that moment when the Manor explains how much attack dino drones to hunt down Lizard People cost that Fred speaks up with the quote, “If we’re looking for places to cut back, then I say racism is the most expensive luxury we have.”

Unfortunately, this political commentary is scattered throughout a story with too many plot threads, resulting in a loss of focus. Wilma take on a job as a set designer  for a movie and where Fred and Barney sneak into films about women. Wilma’s job provided a resolution to the political story line, but Fred and Barney’s viewing habits are left as a dangling plot. While at first the innuendo of Fred and Barney’s viewing appears illicit, Russell deftly reveals they are going to dramas like Bridges of Madistone County. This plot line lacks a resolution or payoff in this issue, but does provide Russell with a narrative hook to talk about the challenges of male and female communication. Hopefully Russell has plans to return to this in a future issue.

for a movie and where Fred and Barney sneak into films about women. Wilma’s job provided a resolution to the political story line, but Fred and Barney’s viewing habits are left as a dangling plot. While at first the innuendo of Fred and Barney’s viewing appears illicit, Russell deftly reveals they are going to dramas like Bridges of Madistone County. This plot line lacks a resolution or payoff in this issue, but does provide Russell with a narrative hook to talk about the challenges of male and female communication. Hopefully Russell has plans to return to this in a future issue.

The fourth plot line deals with the death of a character and is one of the few times that Russell has referenced events from prior issues. The emotional impact of this death may depend on how familiar readers are with the former plot, but the reactions to the loss only briefly allude to the bond of friendship in times of oppression and the shallow acceptance of consumerism.

Russell’s successful political commentary walks a subtle line of being poignant, but not taking any cheap shots at any real world figures or political parties. But Russell’s writing of a character’s death appears to miss an opportunity to deliver a criticism on disposable consumerism. Striking the right balance of social critique that is not heavy handed, and yet is not too subtle is difficult to continually pull off. Overall Russell’s The Flintstones remains socially relevant, but this issue’s valuable gems of commentary are obscured through the pile of story threads.