To say that Superman formed the foundation and tropes of the superhero genre would be an understatement. I originally had multiple paragraphs about this, but I can sum it all up in one crucial sentence: Superman’s pretty important, guys.

Everything superhero comics have done, are doing, and will do, Superman probably did it first. Secret identity? Check. Flashy costume? Check. The love interest that the hero can’t divulge their identity to, creating decades worth of stories surrounding an overly-complicated romance that could be resolved with a single conversation? Check. The supervillain? Check. Well, not entirely. Not at first anyway. I’ve been reading the original Golden Age Superman stories recently, and a particular character caught my eye.

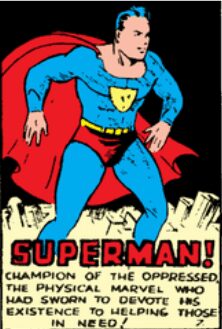

Before he was Man of Steel, Jerry Siegel & Joe Shuster christened him Champion of the Oppressed. A hero more concerned with the needs of the average citizen, and destruction of the elite’s oppressive ways than with killer robots. There’s no contesting it, it’s right there in the first page of Action Comics #1.

It’s no question that his more fantastical elements introduced in his later years are what made him so iconic. However, Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither was Superman. The original version didn’t fly, he wasn’t vulnerable to Kryptonite (on account of it not existing yet), only had enough strength to lift cars, and he just punched criminals rather than melting their Tommy guns with heat vision. However, setting him apart from the modern version of the character we all know and love, he was an inherently socialist character. He fought war profiteers, negligent mine owners, reckless drivers, gang bosses, and sadistic prison wardens. Not supervillains.

At least he didn’t until Action Comics #13 , “Superman vs. the Cab Protective League”.

To understand the importance of this story, we have to note its importance in the superhero genre as a whole. At this point in the canon, the fifth-dimensional imp with magic powers is 5 years away. The green sentient robot who collects cities is 19 years away. And the grey hulking rage monster with rock spikes on its back is 53 years away. There’s no such thing as a “super”villain yet for Superman (or any hero at this point), only villains.

Action #13 starts out the same as any of the other stories of the time. Superman discovers a social injustice occurring, and then decides he’s going to stop it. In this case, the titular Cab Protective League is coercing independent taxi companies to join the League. Superman spends the rest of the story destroying the League, taking down its top dogs and ultimately succeeding. There is no foreshadowing or any sort of implication that the League is led by someone extraordinary.

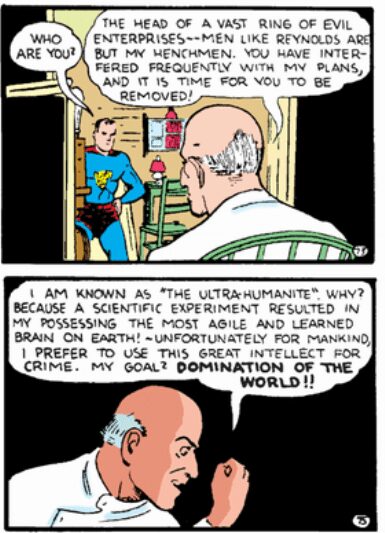

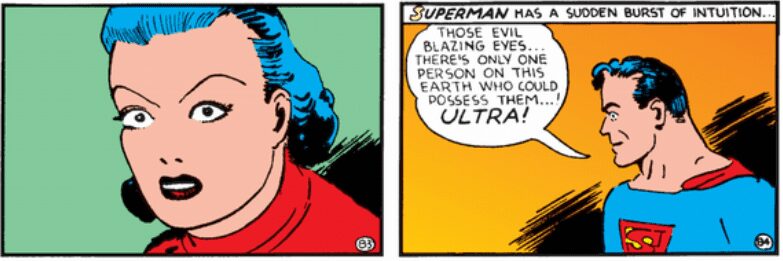

That is until Superman follows a League goon to an abandoned building, who seems to be entirely confident in his ability to confront the Champion. That is because the goon is protected by his boss: a wheelchair bound, bald super-genius known as the Ultra-Humanite.

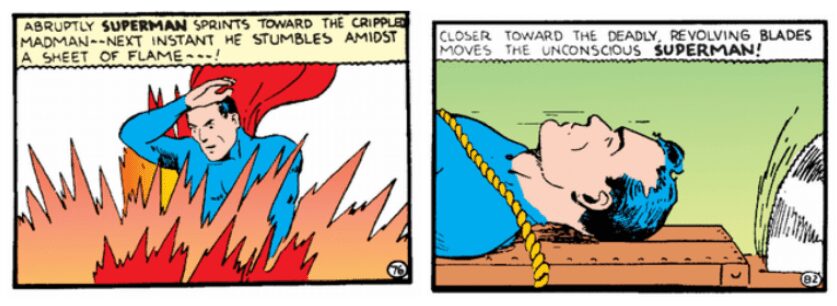

At first, the Ultra doesn’t seem to display any immediate traits of super-villainy. He’s just a white, old, bald scientist (more on that later) who on top of it all, can’t walk. But when Superman tries to apprehend him superhero comics change forever in just the span of two panels: an electrical charge set under the floorboards knock him out. Ultra’s goons tie Superman to an electric table saw and try to slice through his head (this fails, obviously).

This was a new type of villain, one the hero can’t easily defeat, who uses extremely dangerous and gimmick-y methods of action rather than a simple punch or shot to the head. Defined by his egomaniacal spirit and cartoonishly evil ways, Ultra proved he’s not here to play. He ‘s prepared to fight Superman, and is prepared to do so multiple times.

Because what really defines a comic book villain, other than their powers or entertaining costume design? Their ability to return to the story, and pester the protagonist again and again, setting themselves apart from run-of-the-mill thugs that are a dime a dozen. The Green Goblin didn’t become iconic overnight solely due to a single appearance in The Amazing Spider-Man #14. He became iconic because he kept coming back again, and again, and again, and again… and again. By the time he died (the first time), his last act of villainy was murdering the hero’s girlfriend, an act unheard of in superhero stories back then. And even then, he came back to life years later, and came back again, and again, and again… and again.

It’s what puts your Jokers, your Venoms, your Darkseids, and your Lokis on another level. There are many superhero stories where the writer purports that they’re introducing “the next big villain in a (superhero)’s life”. The villain shows up once, and punches them harder than that hero’s ever been punched before. But somehow, that villain never breaks into the mainstream, or becomes an A-Lister, or shows up in a blockbuster. They’re overhyped and overwritten in that one story… and they don’t come back. In the medium of serialized storytelling, repetition is what makes concepts stick in the mind of the audience. It’s why the Batmobile is considered a staple of the DC mythos, and Batman carrying a gun isn’t. Because barely a year into his 80+ year history, they stopped making Batman carry a gun. The Batmobile still appears in comics and movies to this day. Plus, it looks cool.

It’s that same element that set the Ultra-Humanite apart from the lesser goons of Superman comics. Ultra returned for 5 more issues of Action Comics for a sorts of “story arc”. A staple of Ultra-starring stories was that unlike the common gangsters Superman would collar in at the end of the story, Ultra always got away. With inventions such as invisible cars, holograms, and the creation of a deadly plague, he was always ready to throw something new at Superman for him to overcome.

At this point you might be thinking: What does any of this have to do with Ultra being trans? That element is introduced when Ultra seemingly dies at the end of Action #19. While that might have been the end of the character as we knew him, Action #20 starts out with the revelation that he had his henchmen transfer his mind to that of Hollywood starlet, Dolores Winters.

While it would be easy to invalidate the argument of this piece with “Siegel & Shuster probably didn’t mean to do that”, because the truth is, they probably didn’t, stories are meant to leave some room for the readers to draw their own conclusions. So let’s humor that proposition and wonder: What exactly are the implications of this plot point?

For starters, why did Ultra decide to transfer his mind into the body of a woman, rather than that of an equally successful man? The story says this was the convenient choice, as he (or rather, she, now) needed to inhabit the body of a successful socialite while also not arousing suspicion. Ultra at no point in the story seems to display any dislike over being a woman. She rather enjoys it, expressing appreciation for her new youthful and able physique as opposed to her old flawed body that she did not feel comfortable living in.

More notable is that in the next (and last) story featuring the original Ultra, Action #21, all narration boxes and dialogue are rewritten to refer to the character as “she/her”. To trans people, being referred to by your prefered pronouns is not just common decency, but empowering and validating after (usually) spending the majority of their lives being addressed by the wrong pronouns. Ultra shows no displeasure at being addressed as a woman, and even Superman himself spends the entire story referring to Ultra as “her”, despite addressing the villain with male pronouns in the previous encounter.

Everyone is on board with using female pronouns for her, and the entire story goes by without much attention ever going to the fact that Ultra originally lived in a male body. All in all, these elements make for a surprisingly modern and progressive whole, especially for a story written in the late 1930s. Unfortunately, Ultra would die at the end of Action #21, and it would be decades before the character took center stage in stories again, fading into obscurity. The unfortunate side effect of being the first supervillain is that a lot of Ultra’s traits were then perfected by others.

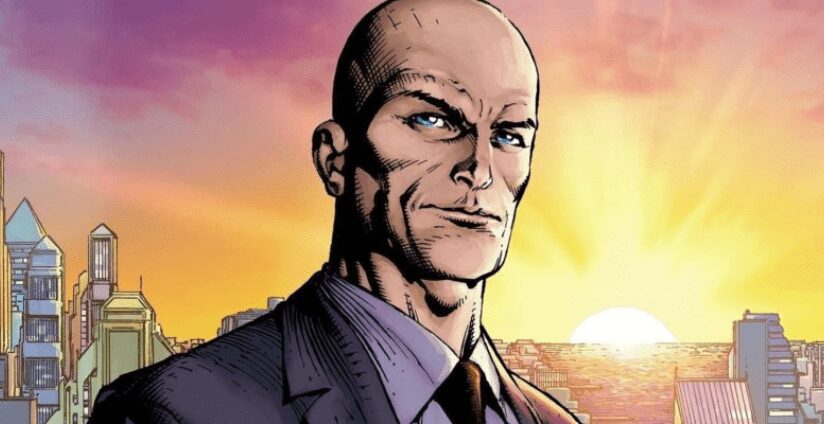

Remember that earlier bit where I mentioned Ultra’s original male appearance was as a white, bald mad scientist? Who else does that remind you of?

Lex Luthor, undeniably the Superman villain, was introduced in Action Comics #23, exactly 10 issues after Ultra’s debut. Since Lex didn’t die a few issues later, but rather, as noted before, kept coming back, cemented himself as the new recurring bad guy that Superman could never beat. Ultra was brought back through the Multiverse approach as one of the villains of “Earth-2”, the universe where DC’s original 1940’s stories occured. Her first major reappearance was in 1980, still in Dolores Winters form (and being addressed as she/her).

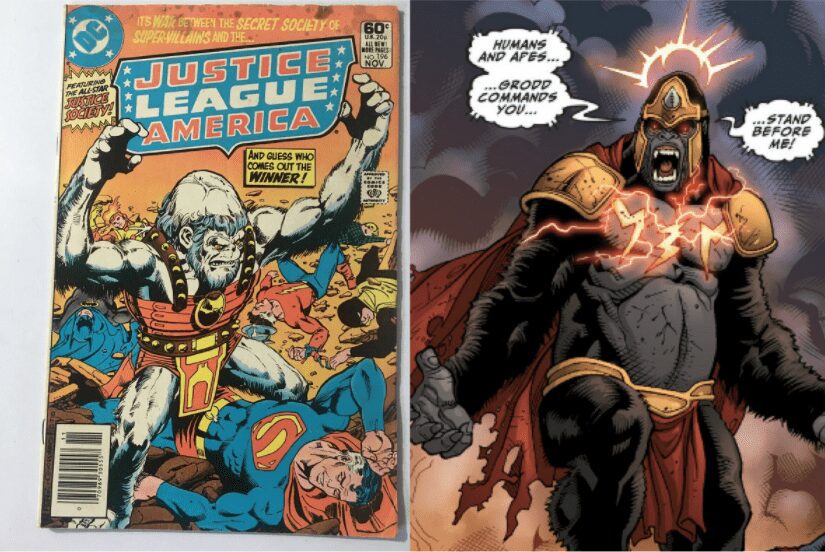

In the following years, writers played with the mind-switching McGuffin freely, even making Ultra control the body of an ant at some point. However the biggest use of this was in a 1981 Justice League story, where Ultra transplanted her conscience into a gorilla, becoming a super smart animalized villain. The thing is, similarly to the way Luthor replaced Ultra as “the mad scientist” back in the 40’s, DC already had a super-smart gorilla…

So over the years Ultra’s presence in the DC universe was downplayed by more and more writers. They still featured in stories, but never quite reaching the heights of super-villainy and A-List prominence of their original appearances. It’s not hard to understand why either, as their presence would seem redundant with the aforementioned existence of Lex and Grodd, widely considered to be much more compelling and iconic characters.

While Ultra may never soar again in the pages of DC as an important character, or delve into the questions of gender identity and transness the concept so clearly invites, it’s interesting to note how a character created more than 80 years ago could have such a modern concept baked into their story, even if the original creators didn’t intend it to be so.