Duck and Cover #1

Melodrama

Writer: Scott Snyder

Art: Rafael Albuquerque

Colors: Marcelo Maiolo

Letters: Bernardo Brice & RAD

The world of therapy often uses the word FEAR as an acronym for the phrase “False Evidence Appearing Real”. And while this interpretation is often helpful to those attempting to overcome a phobia, it also creates a negative and limiting connotation. Especially when you consider that the phrase is applicable to many stories, even comics, that exist to entertain or inform the individual instead of frighten them. Of course there are some works that do all three, as is the case of Dark Horse Comics new series Duck and Cover. But that makes perfect sense once you consider the source.

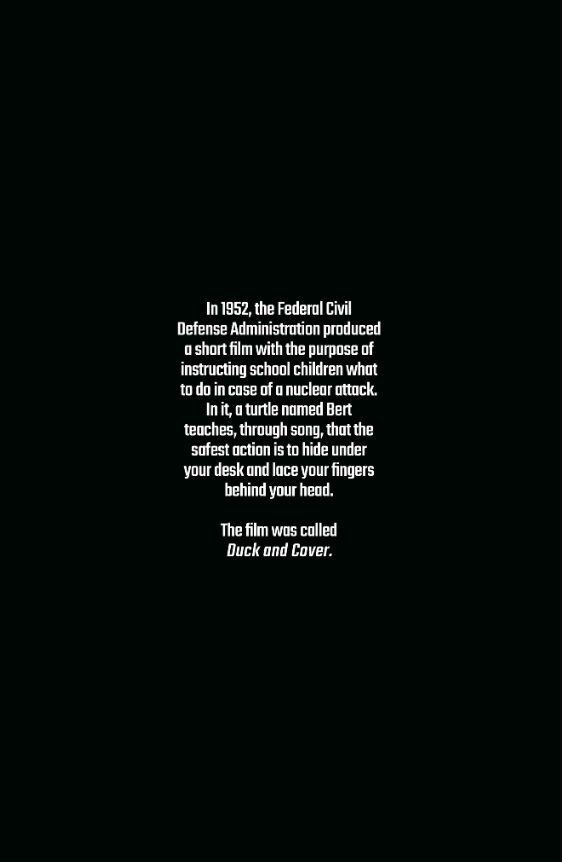

For those who have never heard of nor seen the original, Duck and Cover #1 features a lettered splash page from Bernardo Brice & RAD that provides pieces of the backstory behind the creation of the 1952 film Duck and Cover. Part animation featuring a turtle named, part live action scenarios involving school children, through narration and song viewers were supposed to learn what to do in the event of a nuclear strike that fueled the fears of the Cold War.

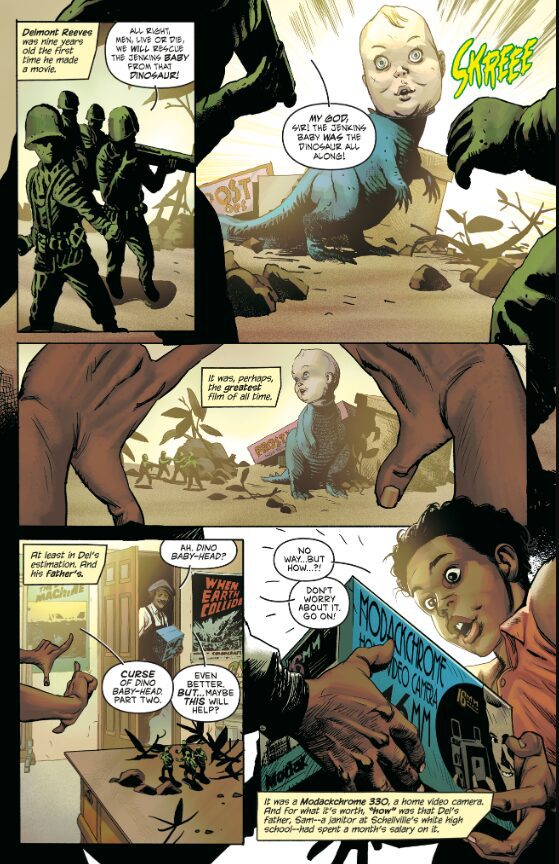

Similar to the 1952 film that this comic owes at least a small portion of its creation to, Duck and Cover #1 features an unseen narrator. But instead of Bert, the first actual character readers meet is a black youth named Delmont Reeves. Although the story offers several unique characters, writer Scott Snyder slows the story to fully establish the fact that even at eleven years old Del is a visionary. With dreams of making movies, Del is recognizable as someone who can both conceptualize and capture the complexities of any situation. Which is perfect once you consider the climate of his hometown of Schelville, Colorado in 1949.

After all, although it’s a work of fiction, Duck and Cover #1 maintains hints of historical accuracy, like racism and society, that surrounded the era that influenced its creation. In fact, the friendship that exists between Del, Oliver “Ollie” Ozawa and Junior Jackson offers Snyder an opportunity to establish the characters at an age when we are often oblivious to the troubles of the world. Because as the original Duck and Cover repeatedly reminds the viewer, the attack can happen at any time. And according to the narrator of this comic, unfortunately Del got too caught up in what he was capturing with his Modackchrome 330 camera to notice the town’s stray Doberman until it had cost him his eye.

It is after the attack that the major theme of this issue, if not the entire series, becomes obvious to the reader: Danger Ahead. Like the yellow highway sign, the encounter with Tim McKenna’s dog acts as a warning for what is about to occur in the lives of these three young boys. So when we catch up with them as teens six years later at the drive-in, the differences between them are easier to see. Their tense friendship, along with the antics of a bully named Pug and the attitude coming from Jack, leader of the high school delinquents, end up exploding in a fight that brings in the cops and lands everyone except Del a week of school daytention.

In keeping with main character Del’s career choice, the creators of Duck and Cover have chosen to give the comic a cinematic aesthetic. So if you can imagine this as a television instead of a comic series, the drive-in and all preceding events are the cold opener of the episode. And even if Ollie explains to Del that he is against the particular genre, it feels like. Melodrama is an appropriate title for this issue in many ways. For starters, anyone who watches 1952’s Duck and Cover will notice what nowadays many call overreacting – or actually over acting – in some scenes during the civil defense film.

Instead of exaggerating things in Duck and Cover #1, artist Rafael Albuquerque uses another trick that takes place in the public service announcement – emphasis. Much like the 1952 film narrator made it a point to highlight specific scenarios, Albuquerque and color artist Marcelo Maiolo use the panels to emphasize important plot points. Given the emphasis on the character in this opening issue, this means many scenes highlight Del, or specifically his eyes and vision.

From his introduction that shows him framing the film’s shot in his childhood bedroom and when Pug sends a cup of soda flying and it hits him in the face at the drive-in. Even as he sizes up the situation before heading into daytention in an effort to save his father’s job at the “white” school, Duck and Cover #1’s artistic team provides readers with Del’s emotional reactions to what he is witnessing. Especially after the events that bring this first issue to a close.

While 1952’s Duck and Cover mentioned a warning would sound before any of America’s enemies dropped a bomb, Dark Horse Comics series’ narrator explains that after years of nothing but fear mongering people began to ignore the sirens. When you consider that schools during the time did drills similar to today’s fire and active shooter scenarios it is easy to understand how people, especially children would stop paying attention. But as Bert’s narrator reminds the audience several times, and as we see in this first issue, seeing is believing. So when you notice the flash you know what to do…it’s time to Duck and Cover.

Score: 8.8