On January 26, The New York Times announced that it will discontinue some of their print and online bestseller lists effective February 5—among them were ones for graphic novels and manga, which will now be included in general fiction categories. Noting that those being eliminated were introduced as an experiment, a spokesperson told EW:

We will continue to cover all of these genres of books in our news coverage (in print and online). The change allows us to devote more space and resources to our coverage beyond bestseller lists. . . . Readers will be notified that individual lists will no longer be compiled and updated by The New York Times on the relevant article pages.

Some graphic novel creators (writers and editors) expressed their concern after hearing the news.

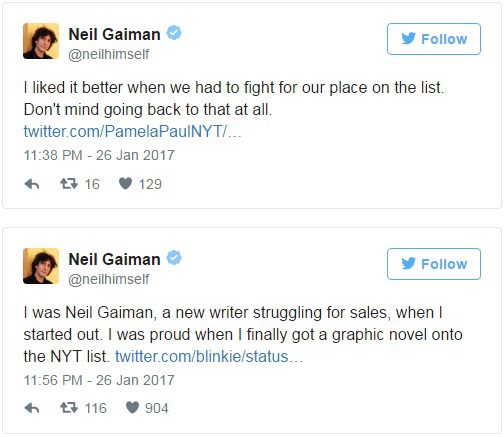

Neil Gaiman, author of many books, comics, and graphic novels, including the award-winning graphic novel The Sandman, took to Twitter:

First Second Books editor Mark Siegel said, “Moving to eliminate the Graphic Bestseller lists seems like a misreading of the medium’s importance and its ever-growing interest to readers.”

Leigh Walton, Top Shelf editor, noted, “The Times may not fully realize how significant their list has been to the development of our art form.”

Although it may not be The New York Times’s intent, by eliminating comics from the bestsellers list, it seems like another way to discount their value. Not to mention, discontinuing graphic novels from the bestsellers lists runs counter to recent trends, with NielsenBookScan numbers showing that sales increased 12 percent in 2016. However, this decision feels more like a snub, as society has looked upon comics as not “real reading” for decades—perhaps due to the blending of words and images, which can appear “childish” to some. Although graphic novels like Watchmen, Persepolis, Ghost World, The Sandman, and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen have received praise, there is still an unfortunate stigma attached to comics and to being a comic reader.

Scholastic defines it this way:

Some parents and educators may feel that graphic novels are not the “type of reading material” that will help young people grow as readers. They may cling to the belief that graphic novels are somehow a bad influence that undermines “real reading”—or they may dismiss graphic novels as inferior literature, or as “not real books.”

But as educators have found, in addition to promoting recreational reading, graphic novels have the ability to enhance vocabulary and understanding of advanced themes in literature and visual literacy.

As the preeminent ranking of the bestselling books in the United States, The New York Times’s bestsellers list was a place where graphic novels and manga received the credit and recognition they deserved. Removing them feels like a setback to an industry that has fought to gain momentum.